As a once-upon-a-time-ago student of Competitive Dressage, this term is very familiar. As a student of Classical Dressage this term is foreign. But why? Do you know what “on the bit” means? Can you put it into words? What does being “on the bit” do for you and your horse? What does it lead to?

Don't have an answer to these questions? You aren't alone. The term “on the bit” doesn't have an origin in the long-time history of Dressage, but according to Bettina Drummond it is an orphan that is only causing chaos, confusion and much of the demise of Dressage.

I found this great article at Eclectic Horseman written by Dr. Max Gahwyler and Bettina Drummond which talks about the origins of “on the bit” :

There is no other statement used so often in Dressage riding as the horse should accept the bit, be on the bit, etc. And very often when you go to clinics or shows, it's the predominant preoccupation of riders, trainers and, unfortunately, often also the judges. It is the foundation of Dressage riding in our country, and this should be just the reason why we should step back and have an unbiased look at what it does to Dressage riding (and why so many of our horses and riders get stuck or break down in the 1st or 2nd Level.)So our next step is to go back to the countries where our present day Dressage originated 500 years ago, such as Portugal, Italy, France, Germany, Austria and Sweden, and scrutinize the literature in the original language and meaning, and not in the English translations, which are all very recent. Even the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI) and later the American Horse Show Association (AHSA) Dressage Rulebook were only put into English in the 1920s. But, no matter how hard you look, even going back to the 15th and 16th century, you do not find any expression equivalent to “On the Bit.”

This expression, if you like it or not, fixes the attention of riders, trainers and judges on the head carriage and frame in front as the symbol and hallmark and primary objective of Dressage and training. Instead, the frame in front should express the engagement and throughness from behind and the rider in harmony with the horse on the aids; the frame in front should not be the result of hanging on the reins. It is well expressed in the German Federation statement that the horse seeks the contact and the rider provides it, not the other way around, since pulling the horse into a vertical head position has nothing to do with collection. On the contrary, it prevents engagement and develops nothing but an insensitive, unresponsive horse on the forehand and does not allow for an expressive movement in self-carriage.

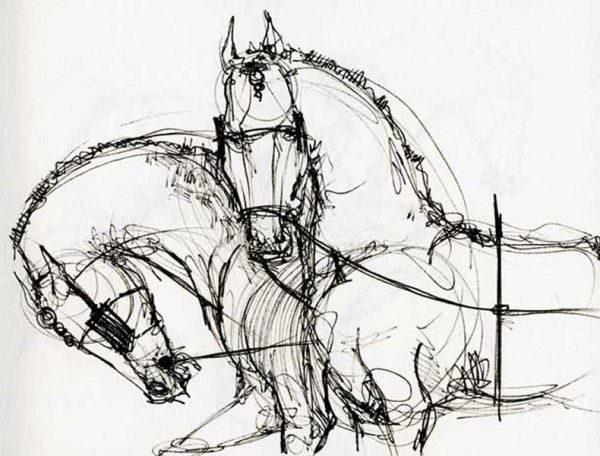

The concept of collection and elevation in front. The lines behind the horse show the progressive flexion and engaging of the hindquarters. Wilhelm Museler from Reit Lehre 1928.

That brings up the subject of maintaining a sensitive and soft mouth, which goes back to the school of Naples. It was then clearly realized that in training a young horse, harsh rein action would occur, either inflicted by the rider, or the self-defense of a young horse, and the sensitivity of the bars would be progressively damaged. Let's face it, a piece of steel in the mouth that is pulled on unilaterally or on both sides with the connection of the snaffle joint pushing against the palette is no treat. Also for about 6,000 years all snaffle bits had cheek pieces, so when using one rein, the cheekpiece of the other side prevented the bit from slipping through the mouth and pushed the head in the desired direction. More recently invented loose ring snaffles are not a step in the right direction.So when you read the book of Johan Batista Galiberti, written in 1610 and translated into German in 1660, Galiberti, a pupil of Grisone and Piniatelli, recommends the training of the horses first in a caveson or hackamore until the basics are established and only then progressively introducing a bit. In addition, the reins to the bit are held in the left hand, which is always softer, and never used. Training continues with the caveson in the right hand until the horse is made light and in self-carriage. At this time, the caveson is progressively dropped and the connection established through the reins to the bit. But since the bit was never used for the training, the sensitivity and lightness was maintained and the principle of the Descente de Main evolved as used in the Ecole de Versailles and later became beautifully described by Robichon de la Guérinière and DuPaty de Clam.

Interestingly, a few years ago, the riding manuals of 1720 of the Royal Spanish Riding School, which were believed lost, were rediscovered in Vienna. And here again, the training of the young Lippizzaners was done in a caveson without a bit, which was only introduced after they had reached a secure level of training.

The remainder of this concept can still be seen in some lunging cavesons from Europe, having in addition an adjustable snaffle bit. These cavesons were common 50 years ago in Europe, but were never available in the United States where the concept of preserving a sensitive mouth was never a primary objective of Dressage training. However, in a young horse trained like this neither the lunge line or initially the side-reins were attached to the bit, so the introduction of the steel bit was a process of slow, gradual acceptance without any pressure. Later in the training, long side reins were attached to the snaffle, but never the lunge line, which only pulls the bit up or out of the mouth. Doing this is an abuse of the horse and only done by uneducated and insensitive horsemen.

Very few people have ever made or experienced a horse with a truly sensitive mouth, as neither trainers nor riders are concerned with this, as it is not part of the present culture of “On the Bit” in the U.S. In addition, the early introduction of the double bridle, not to speak about draw reins and other devices we see so often, is the hallmark of incompetence as well described by Udo Burger.So how did the English term “On the Bit” appear in our terminology? To the best of my knowledge, it started with the creation of the FEI, which took place in 1921, initiated by General DeCarpentry with the assistance of Dr. Rau and the German General Halsing Bersett.

General DeCarpentry wrote the FEI rules and definitions in French as we see them today in the FEI rulebook using the sophisticated French Dressage vocabulary with its infinite nuances and meanings. But nowhere do we find any expression even remotely resembling our notation of “On the Bit.” which would translate in French as “Sur le Mors,” an expression which simply does not exist.

The Germans never translated the French FEI text, understanding most French and having an eloquent and well-established equestrian vocabulary of their own as demonstrated in their rule book and the publication of Basic Principles of Riding and Advanced Techniques of Riding by the German Equestrian Federation. Nowhere do we find anything in the original German version close to our statement of “On the Bit,” which is only occasionally used in the English translation for lack of any other expression. So why does this definition of “On the Bit” come up in the English FEI version which became today's AHSA Dressage Rules and definitions in the official rule book?

Since there was hardly any Dressage in the early 1900s in England or in the United States, nor any English books on Dressage or magazines, there were simply no real equivalent terms for the statements of DeCarpentry, not to speak of reflecting the nuances of meaning of the French Dressage terms. I do not know who translated in the 1920s to ‘30s the French FEI text into English. It is eminently clear that the translator had a fairly good grasp of French but not of the French equestrian terminology, and the term “On the Bit” was created without really understanding what was meant in French or how this newly created definition would affect riding in English-speaking countries.

Lacking any other source of information, this FEI text was taken over by the AHSA and is still the official version which we see today in our rulebook, including the statement “On the Bit” without any futher explanation. Also, our AHSA rules reflect primarily FEI requirements, movements and gaits with no really meaningful statement from Training Level to 4th Level. Even recently introduced new movements such as chewing the reins out of the hands are neither referred to nor defined after they were put into our tests six years ago.

Just to show you a quick example of the first few pages of the AHSA rulebook and how this can lead to complete misinterpretation of the original French text of DeCarpentry, article 401-3 states “The horse gives the impression to execute of his own accord what is required of him, etc.” But in article 401-6, it states “In all his work, even at the halt, the horse must be on the bit”-which obviously includes training levels and introductory levels, since there is no distinction made. This in no way represents the finesse of the French Dans la Main (“on the aids”). But in article 403-3, it states that at the walk the horse should not be asked to walk on the bit, and in article 403-4.2, it states that at the medium walk the horse must be on the bit. This makes absolutely no sense, and if you want, you can go through the entire rulebook as far as riding is concerned and find contradictory statements like this one after the other.If in our English translation we would say in article 401-6 that the horse in all its work even at the halt remains obediently under the influence of the rider's aids, this would be closer to the true French meaning and removes the fixation to the hands, the bit and the front of the horse, and leads to a more integrated approach of all aids applicable to this movement.

Using this expression “On the Aids,” we could approach the variability of the French terminology with expressions like “teaching the young horse the progressive acceptance of the aids” up to the FEI levels where it should be on the aids. This includes lightness and self-carriage: not pulled into an artificial frame in front, the emphasis placed on the seat, position, weight, harmony between horse and rider and correct timing and coordination of all the aids. An artificial frame in front does not allow for expressive movement in self-carriage.

But to replace the expression “On the Bit” and banish it forever to oblivion is really no problem, since over the past 50 years we have established a vocabulary of Dressage in America. Terms such as “Acceptance of the Aids,” “On the Aids,” “Throughness,” “Connection,” “Lightness,” “Self-Carriage,” “Swinging Back,” “Relaxation,” “Balance,” and “Engagement,” just to name a few, would much better demonstrate what we really mean and which are really the objectives of Dressage.

Then we achieve what the FEI and DeCarpentry said originally; namely, that the horse gives the impression of doing on his own what is required of him, and not pulled together behind the vertical and consistently on the forehand and never truly through. Unfortunately, we see this all the time from Training Level up to a lot of poor piaffes, passages, piourettes and awful transitions.

Allowing the horse to seek the aids as the older Germans said, or the coordinated aids, aids coming through the back, non-interfering aids, weight aids, seat aids, supporting aids, leg aids, etc. with the horse determining the contact would probably better represent what we really should aim for in Dressage.Also, what further seems to justify to pull together the front of the horse, and often behind the vertical and call it Dressage, are photos shown in European and in American Dressage magazines of winning teams with an incorrect, pulled together, short frame in front. Even though we always speak of Classical Dressage, nobody seems to go back to the original drawings and photos of the past. Interestingly enough, this concept of having a horse in front of you and with a head carriage more in front of the vertical the more it is collected is clearly depicted in the pictures of Müseler, (see diagram on facing page), which were adopted as correct by the FEI as long as Niggli was its chief but have pretty much fallen by the wayside as of now.

On the one hand magazines print the statements of Harry Boldt, Klaus Balkenhol, Christine Stuckelberger, Cindy Sydor, etc, condemning pulling the horse together in front and then publish dozens of pictures showing exactly the opposite, with horses pulled behind the vertical winning competitions. Take a look in one of the many Dressage publications available in the U.S. and judge for yourself. A clear policy and message to the Dressage community could not hurt.

In a more recent example in an article with Christine Stuckelberger said, “Today you see the horses pulled together. This is a mistake. A judge should penalize a horse that is tense and always goes behind the vertical.”

Harry Bolt said, “Regarding horses' necks, I think judges should be more careful that horses' noses are in front of the vertical.”Snydor echoes the comments of many colleagues in adding that an overemphasis on the front end of the horse is another threat posed by poorly trained and performed exhibition work. “If it's too much about the head, neck and front legs, it's bad,” she says. “It may be more spectacular to the uninitiated, but there is already too much emphasis on the front end in regular dressage. We don't need to be promoting that emphasis any further.”

Another reason the scores are so high today is because of the gaits our top horses show, not because of the quality of the execution of the difficult dressage movements. Just look at the horses' mediocre piaffes, passages, flying changes and transitions, etc., we see in all the shows. But the German warmblood has a habit of going forward no matter what kind of head position the rider puts him in, even though this does not represent correct training and pulls him on the forehand.

In conclusion, since we now have a terminology in the United States correctly expressing the objectives of Dressage, maybe the time has come to upgrade our definition and rulebook statements and get rid of terms that not only make no sense but also are detrimental to the future of our sport.

It would be a nice beginning of the new century.Dr. Max Gahwyler and Bettina Drummond; Eclectic Horseman

As a Massage Therapist and NeuroMuscular Therapist, the alignment and focus on the horse's pelvis makes much more sense to me than focusing in the position of the head and neck, although the two do influence one another and are inter-dependent. The state of modern horsemanship is short-sighted, looking only at what is in front of us when riding, than looking at what is underneath us. But, as a bodyworker, I am also reminded frequently that this is not common knowledge and unfortunately is not widely known among the public – yet.

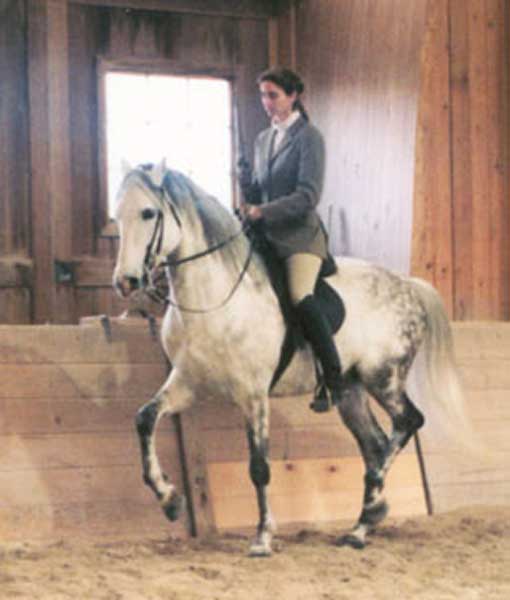

I love the visual in the second image shown above, which illustrates the relationship of the horse's pelvis to his balance point and center of gravity, as well as how it affects the horse's neck posture. In humans there is a similar correlation. If our pelvis is rotated one direction or the other our neck vertebrae will likewise have more or less curvature.

I don't know about you, but when I read things like the above article it gets my blood moving and makes me want to become fluent in french, german and portuguese just so I can pore over the classic literature…

Very nice article! I love the diagram, as I read on a site once a long time ago, you can tell the balance and level of collection of a horse by drawing a line from the point of hip to bit, and if the line slants downwards the horse is downhill or on the forehand. I could never find the site again and this diagram is exactly what I’ve been looking for! 🙂 Although I’m not sure if it applies as much to horses with downhill conformation.

Thank you so much Erika, very nice! have they made copies of the newly found “riding manuals of 1720 of the Royal Spanish Riding School”??

-d

Diane, I have not found any reference to copies of these manuals surfacing for the public. I would be delighted to get my hands on them even just for a once over read – chance in a lifetime! 🙂

Hi Ericak

Maybe Manolo would know about it?

He is great.

Now ,,, let’s talk about the ‘ back end ‘.