The following text inspired me in thought, it is an excerpt from On The Family, written by the Florentine humanist Leon Battista Alberti in 1443. Dated? Yes, but that hardly means it is outdated. It addresses the subject of idleness and the consequence it has on personal achievement.

… Let Fathers … see to it that their sons pursue the study of letters assiduously and let them teach them to understand and write correctly. Let them not think they have taught them if they do not see that their sons have learned to read and write perfectly, for in this it is almost the same to know badly as not to know at all. Then let the children learn arithmetic and gain a sufficient knowledge of geometry, for these are enjoyable sciences suitable to young minds and of great use to all regardless of age or social status. Then let them turn once more to the poets, orators, and philosophers. Above all, one must try to have good teachers from whom the children may learn excellent customs as well as letters. I should want my sons to become accustomed to good authors. I should want them to learn grammar from Priscian and Servius and to become familiar, not with collections of sayings and extracts, but with the works of Cicero, Livy, and Sallust above all, so that they might learn the perfection and splendid eloquence of the elegant Latin tongue from the very beginning. They say that the same thing happens to the mind as to a bottle: if at first one puts bad wine in it, its taste will never disappear. One must, therefore, avoid all crude and inelegant writers and study those who are polished and elegant, keeping their works at hand, reading them continously, reciting them often, and memorizing them … Think for a moment: can you find a man — or even imagine one — who fears infamy, though he may have no strong desire for glory, and yet does not hate idleness and sloth? Who can ever think it possible to achieve honors and dignity without the loving study of excellent arts, without assidous work, without striving in difficult manly tasks. If one wishes to gain praise and fame, he must abhor idleness and laziness and oppose them as deadly foes. There is nothing that gives rise to dishonor and infamy as much as idleness. Idleness has always been the breeding-place of vice …Therefore, ideleness which is the cause of so many evils must be hated by all good men. Even if idleness were not a deadly enemy of good customs and the cause of every vice, as everyone knows it is, what man, though inept, could wish to spend his life without using his mind, his limbs, his every faculty? Does an idle man differ from a tree trunk, a statue, or a putrid corpse? As for me, one who does not care for honor or fear shame and does not act with prudence and intelligence does not live well. But one who lies buried in idleness and sloth and completely neglects good deeds and fine studies is altogether dead. One who does not give himself body and soul to the quest for praise and virtue is to be deemed unworthy of life …

… [Man] comes into this world in order to enjoy all things, be virtous, and make himself happy. For he who may be called happy will be useful to other men, and he who is now useful to others cannot but please God. He who uses things imporperly harms other men and incurs God's displeasure, and he who displeases God is a fool if he thinks he is happy. We may, therefore, state that man is created by Nature to use, and reap the benefits of, all things, and that he is born to be happy …

… I belive it will not be excessively difficult for a man to acquire the highest honors and glory, if he perseveres in his studies as much as is necessary, toiling, sweating, and striving to surpass all others by far. It is said that man can do anything he wants. If you will strive with all your strength and skill, as I have said, I have no doubt you will reach the highest degree of perfection and fame in any profession …

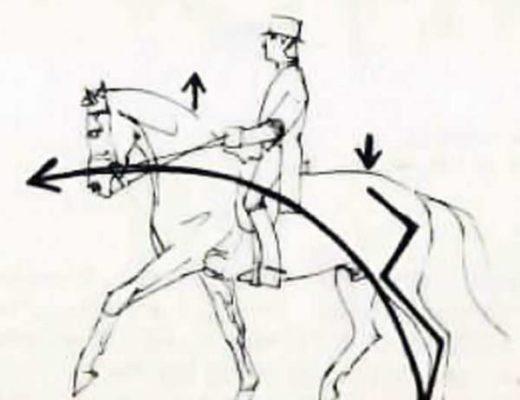

When I read this text I relate it to how idleness can also affect us as equestrians. How often do we allow ourselves to become idle in respect to learning, practicing, staying alert when we work with our horse so we do not ride on ‘auto pilot' and so forth? Do we push ourselves to learn from only the best, the most eloquent of teachers (where a teacher is not automatically synonymous with an eloquent rider), we learn the language and practice it, we look to the sciences involved in horsemanship so that we can make personally well-informed decisions?

Out of that place the quality of fame and wealth is also a genuine place of happiness. Alberti talks about fame and wealth and happiness being synonymous with working hard, but also by being useful to other people. Are you a rider who gives back or do you ride just for yourself without being concerned for the future welfare of horsemanship?

Wonderful questions to ponder on and I would love to hear your own thoughts on this passage and what your own interpretation of it is in respect to horsemanship.